In March 2021, the OCHJS was delighted to receive the collection of family documents, books, prints, pamphlets and paintings formed by the late Joszef Goldschein Gadany, a friend of the OCHJS who sadly died in August 2020. This collection enriches our resources concerning Jewish history in modern Hungary as well as the figure of Benjamin Disraeli. Several works from the collection may be found hanging in our premises at the Clarendon Institute. Additionally, our Leopold Muller Memorial Library received a number of books and archival material on Mr Gadany’s family and personal history as part of the collection.

Below is a gallery of select paintings and photographs from the collection, along with brief descriptions of each, and a history of Mr Gadany’s life written by Dr Paul Dakin, one of the Estate’s Executors and originally published in our 2020-21 Annual Report. If you have any questions about the collection or wish to use/study any of the pieces therein as part of your research, then please email us at enquiries@ochjs.ac.uk.

The OCHJS thanks Mr Gadany for bequeathing his collection to the OCHJS, and his Estate’s Executors—Dr Paul Dakin, Dr David Landau, and Rabbi Dani Smolowitz—for working diligently to ensure the safe transfer and preservation of the collection.

The Goldschein Gadany Collection

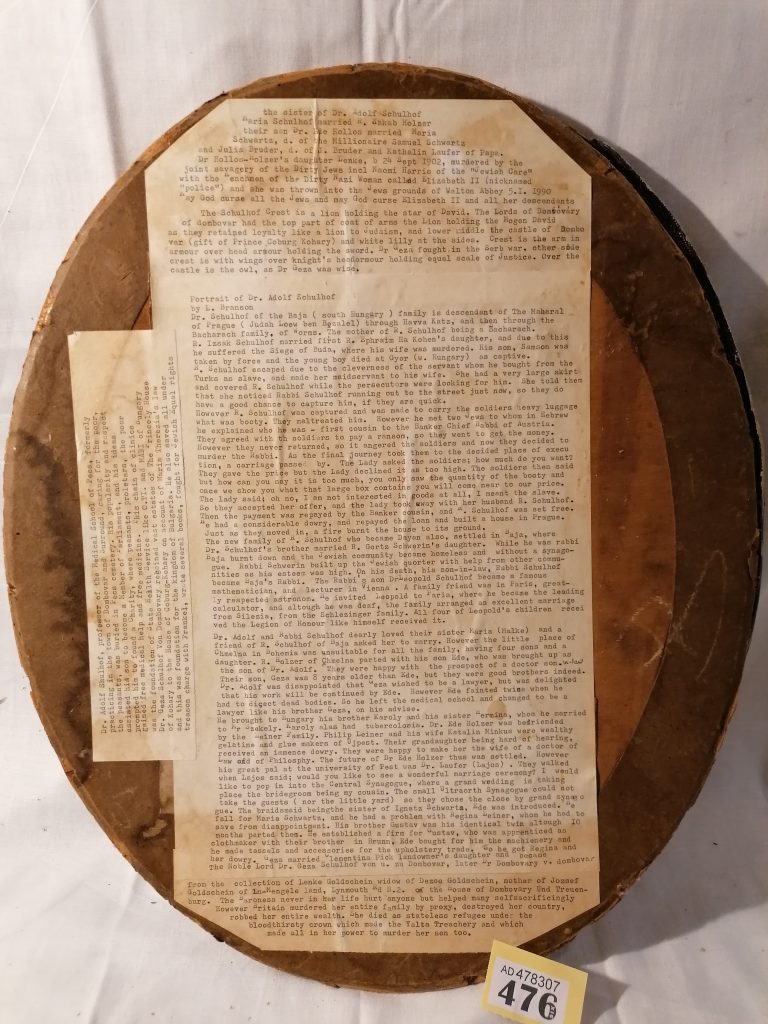

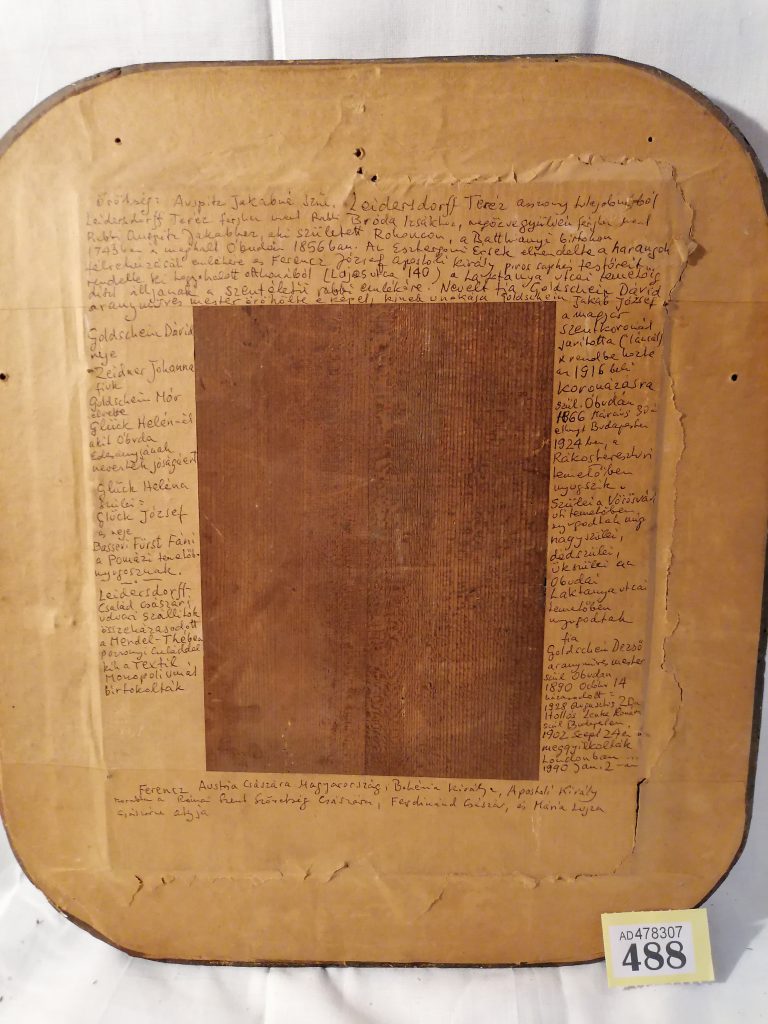

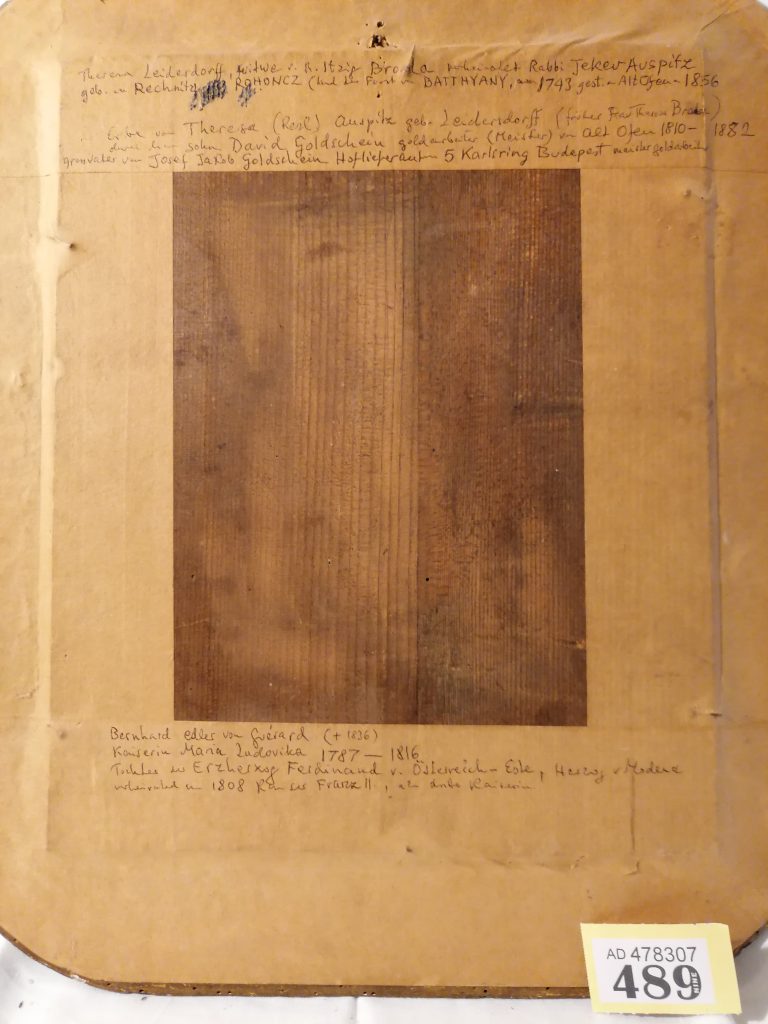

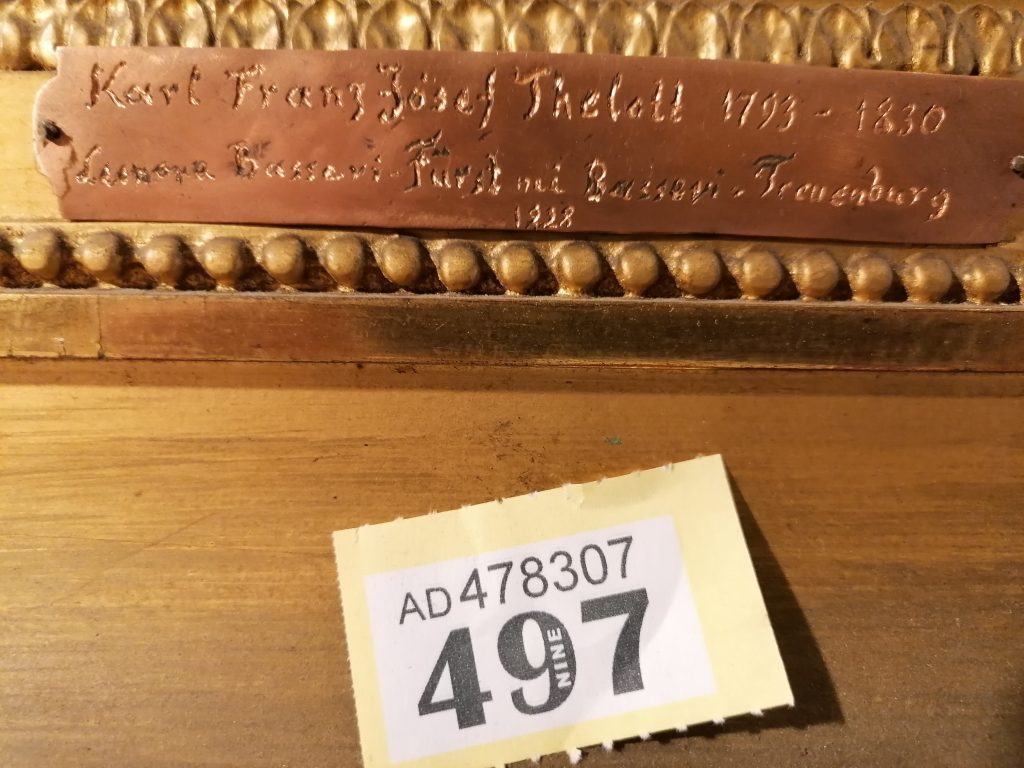

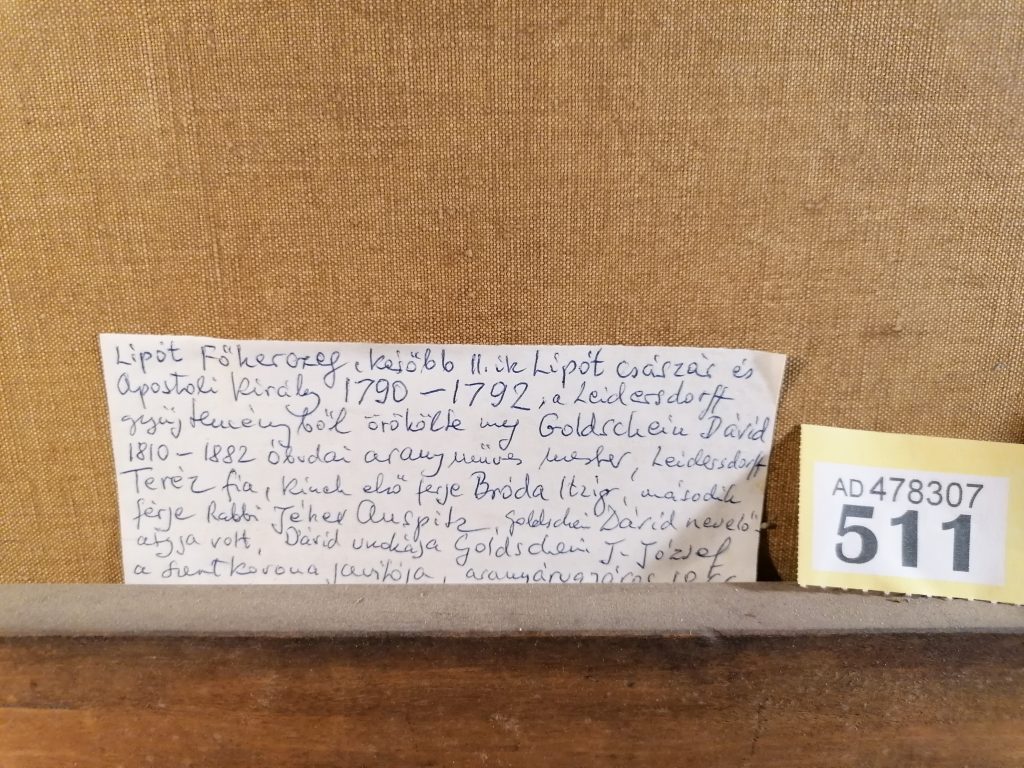

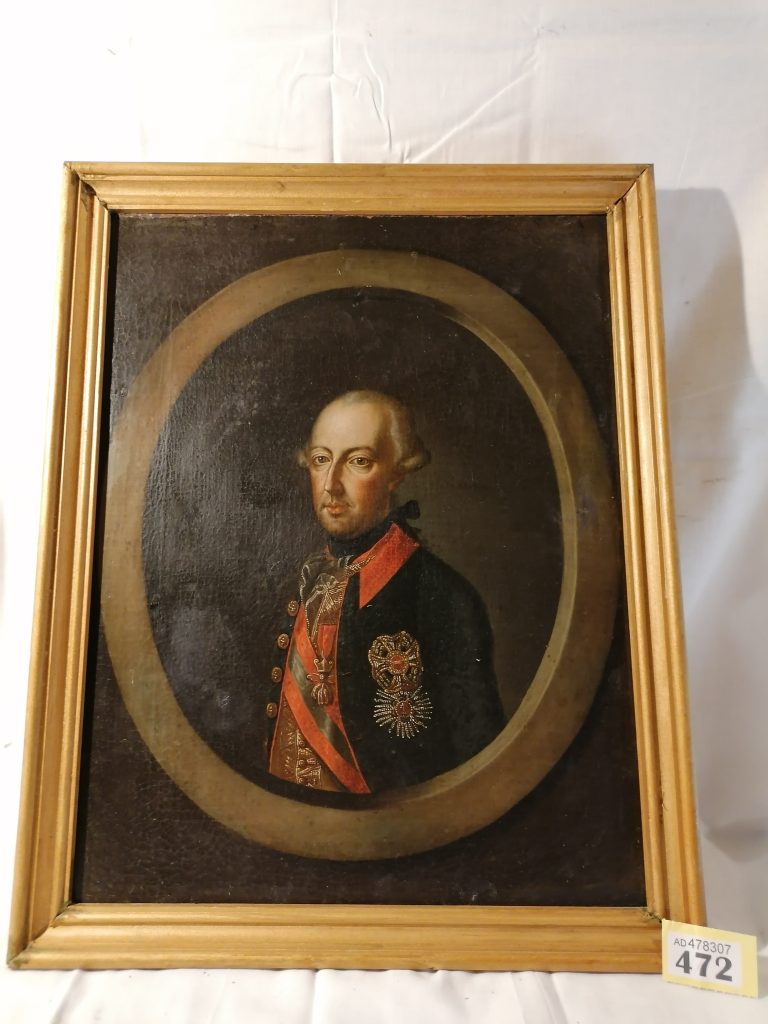

The executors of Joszef Goldschein Gadany’s estate are delighted that the Oxford Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies has agreed to receive his important collection of historic documents and objects. In order to understand the assemblage it is necessary to understand the man. Joszef Gadany, a complex and intriguing character, was born into a well-connected Budapest family in 1931. He developed an interest in his Sephardi ancestors, who had been prominent in Prague and Vienna. A grandfather was appointed Crown Jeweller to the Austro-Hungarian Emperor, while two uncles served at the Imperial Court and one other relative paid for the construction of the Chain Bridge. Joszef, whose father owned a well-known jewellery shop, lived with his family in a comfortable apartment opposite the Great Synagogue, in which his grandfather held a seat of honour at the foot of the pulpit steps. His early childhood was very happy, with holidays spent at his father’s country house by the Danube. After reading Patrick Leigh-Fermor’s memoir Between the Woods and the Water, based on the author’s prewar experiences in Hungarian castles and country houses, Joszef remarked that his parents knew all the people mentioned.

With the rise of fascism and the coming of the Nazis, terrible changes were inevitable for Joszef’s family. His father, who became a well-known and popular officer during the First World War, was shot to prevent him becoming a focus of dissent. Joszef was imprisoned at a young age, and forced into a junior work brigade charged with dangerous tasks such as pulling bodies from bombed buildings. He was rescued, while under armed guard, by an elderly Catholic man who snatched him off the street and hid him in his basement flat. Joszef experienced the terrible reality of the Budapest Ghetto, and later passionately sought to make known some uncomfortable truths omitted from conventional records. He eventually managed to escape and was provided with false papers by a Jesuit priest whose name is now commemorated at Yad Vashem.

Joszef hoped that the Russians’ arrival would improve his situation, but the Communists imprisoned him once again, this time as a ‘class enemy’. Because one of Joszef’s relatives had written the only Hungarian-language biography of Stalin, Joszef appealed from prison to the Soviet leader. An advisor was sent to the prison to thank him for his relative’s work, but when Joszef asked the man to intervene on his behalf the man said that this was a matter for the Hungarian Party. Joszef was eventually released, and he became involved in organizing the 1956 uprising.

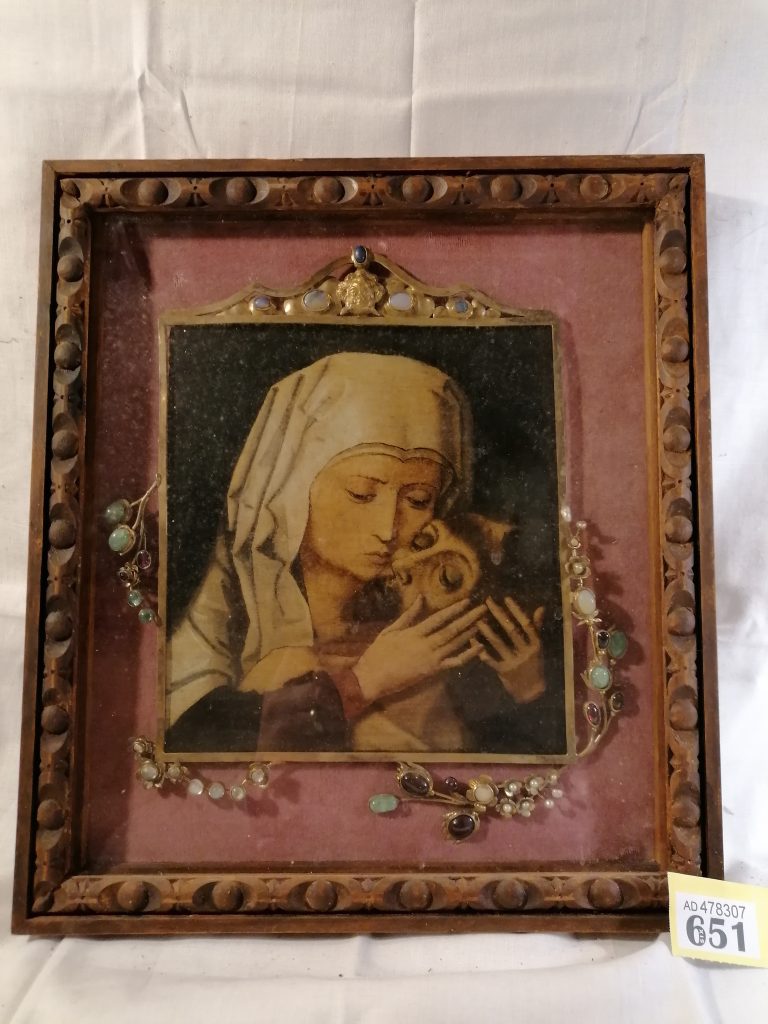

He was reticent to explain his arrival in North London, but it seems that members of the British Government had been lobbied to obtain his release. Settled in East Finchley with his mother, Joszef sought work as an engineer, having had some training in Hungary. When this attempt failed, he followed his father’s example and became a jeweller, opening shops in Bond Street and Chelsea. He was a specialist in enamel work, and a recently discovered receipt shows that he even repaired a Fabergé egg for the Queen.

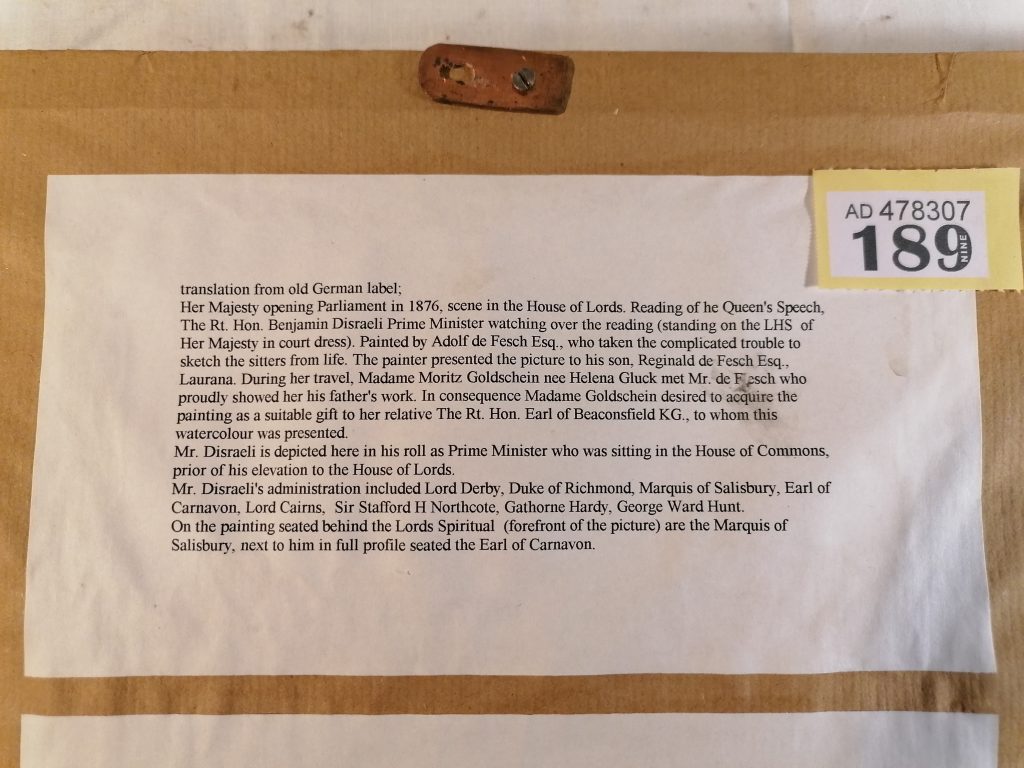

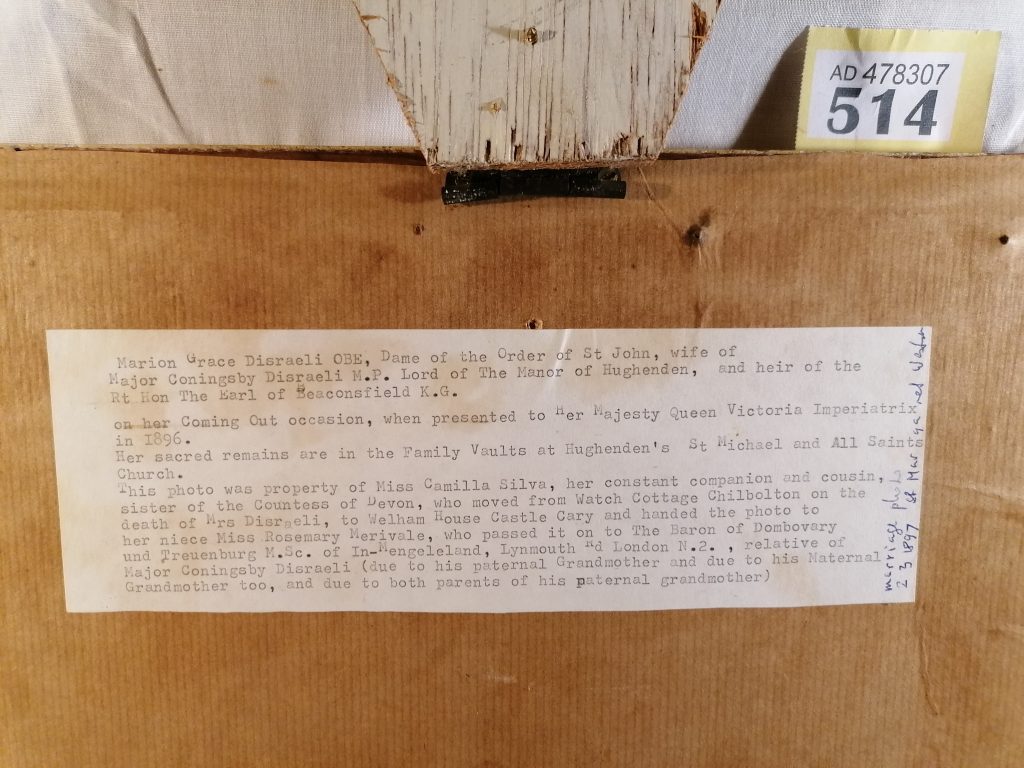

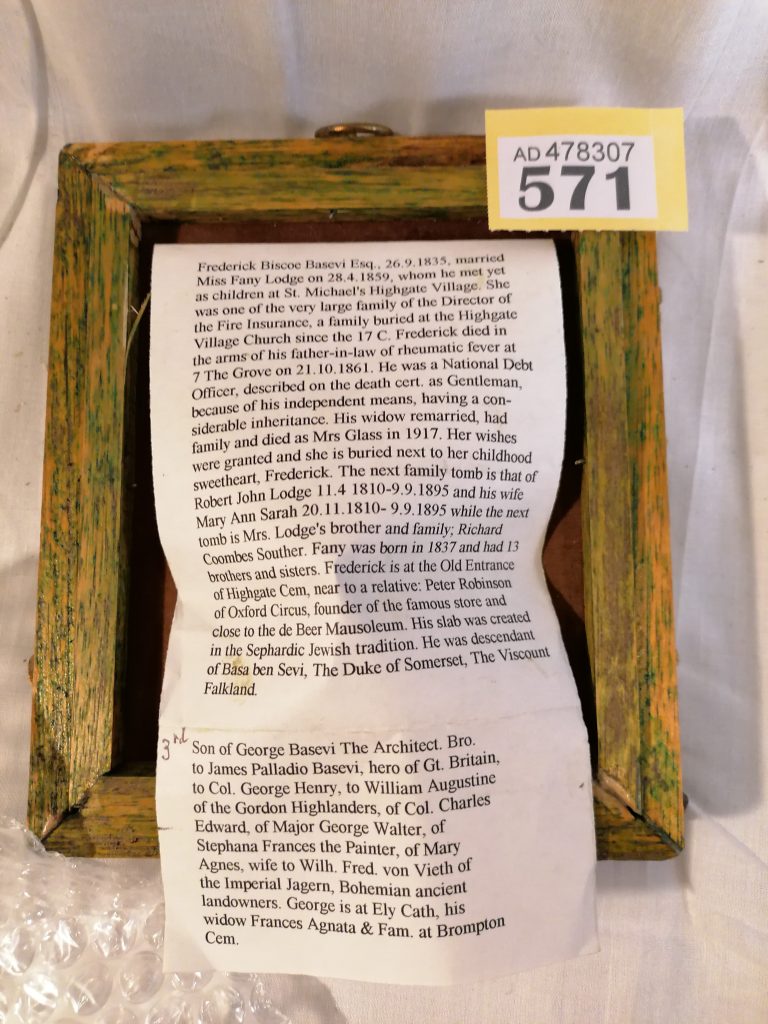

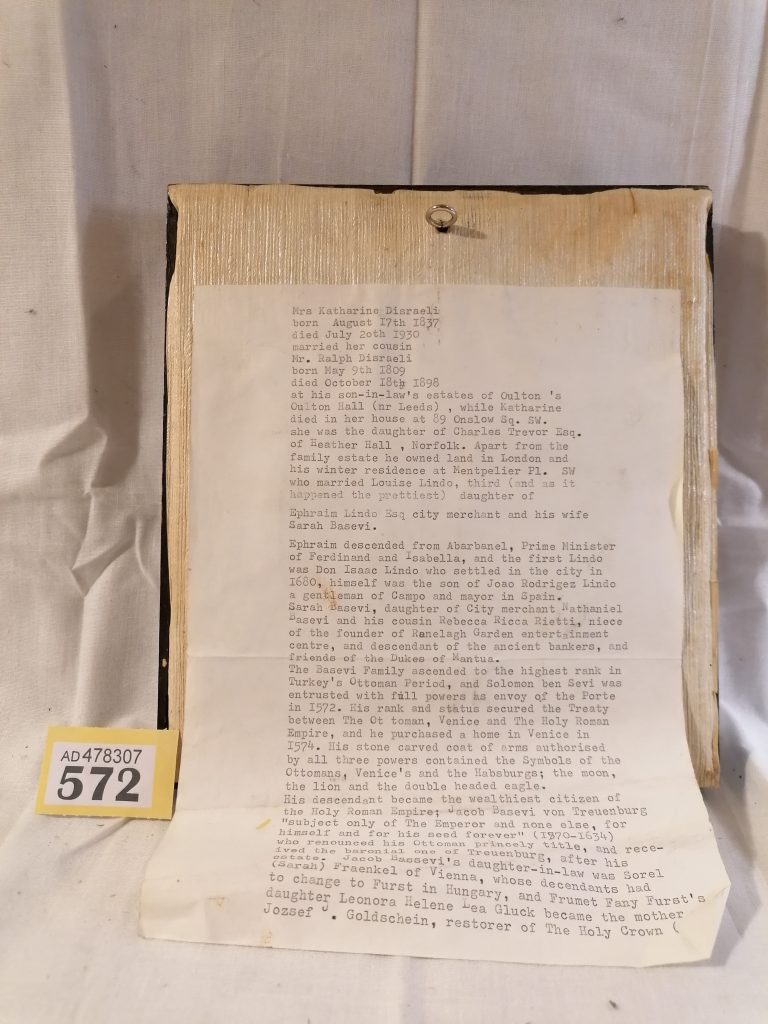

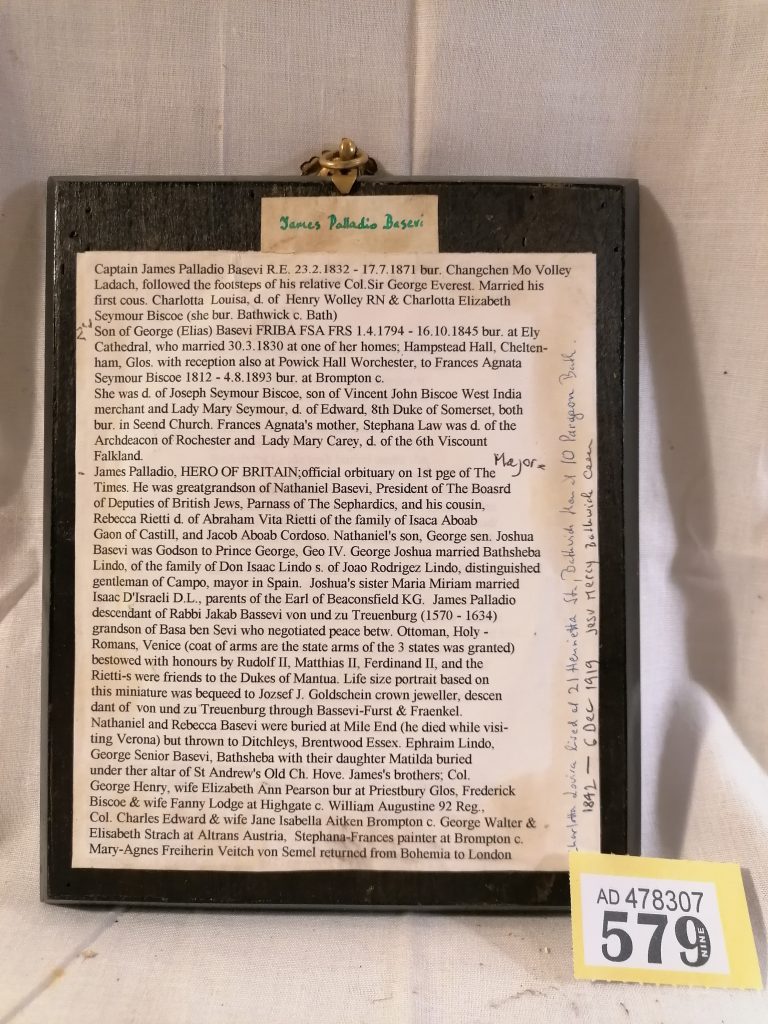

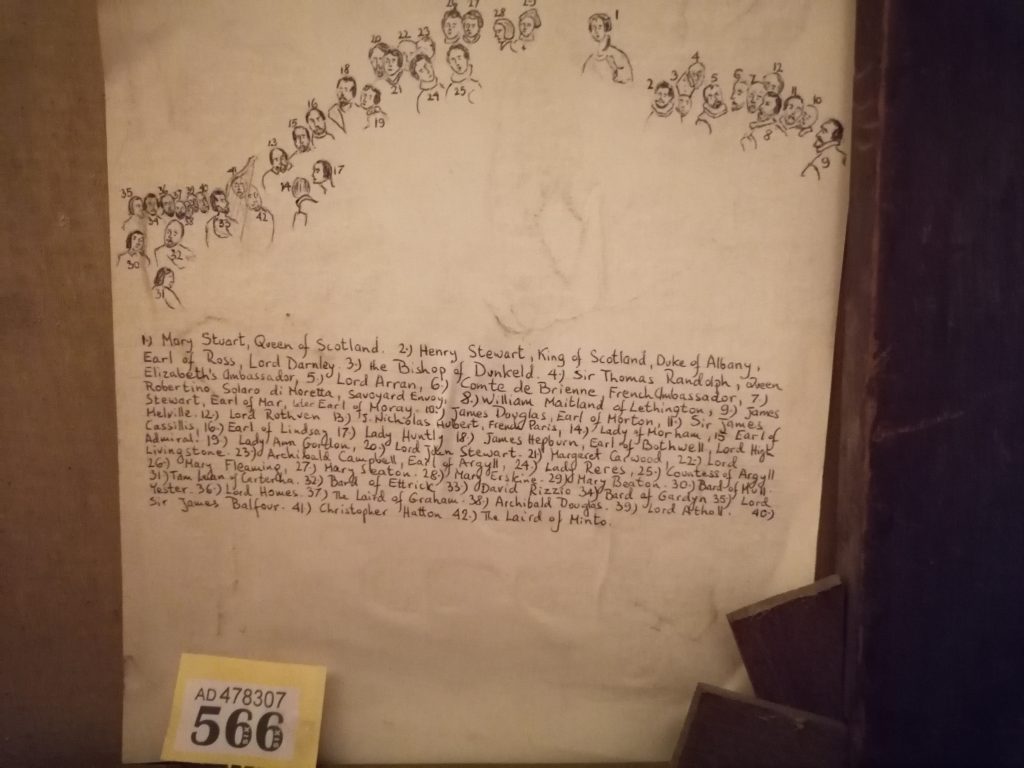

Joszef was fascinated by his family’s history, claiming ancestry from the Maharal of Prague, and connections with Queen Adelaide and Benjamin Disraeli. He was born Joszef Goldschein, but used the title Baron Joszef von Treunberg und Dombovar, uniting honours bestowed on different parts of the family by two Emperors. He had a phenomenal memory and could recall and recount intricate links between individuals, families and royal houses throughout Europe. Subsequent research into such stories, however outlandish they seemed at the time, always proved them correct.

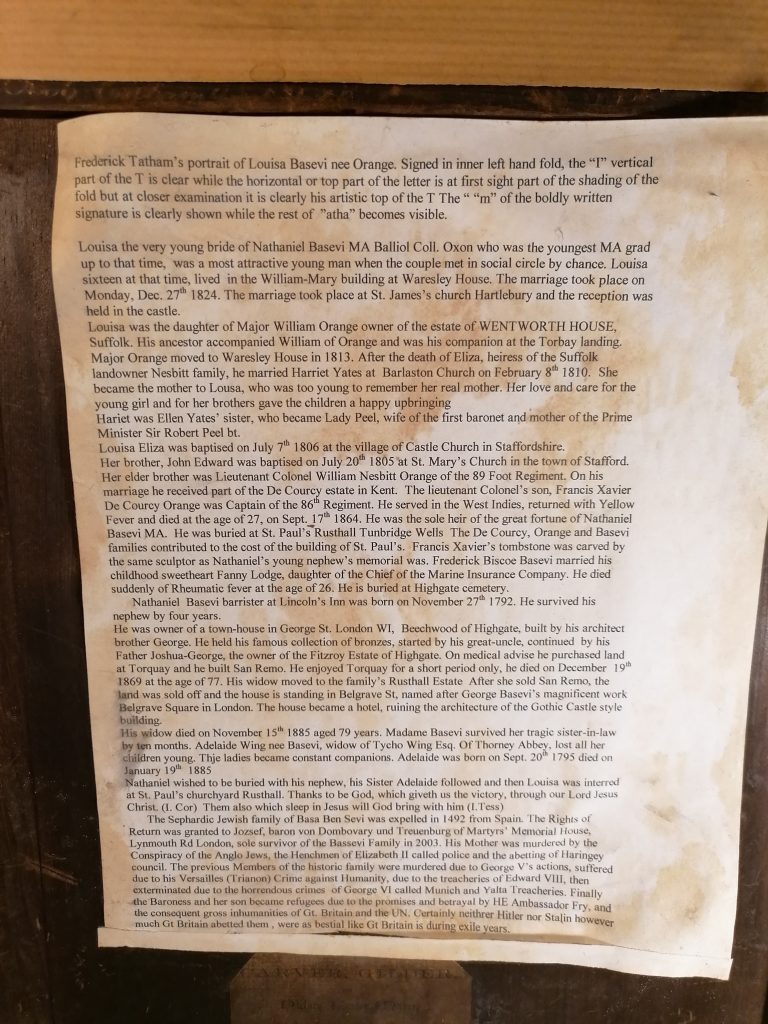

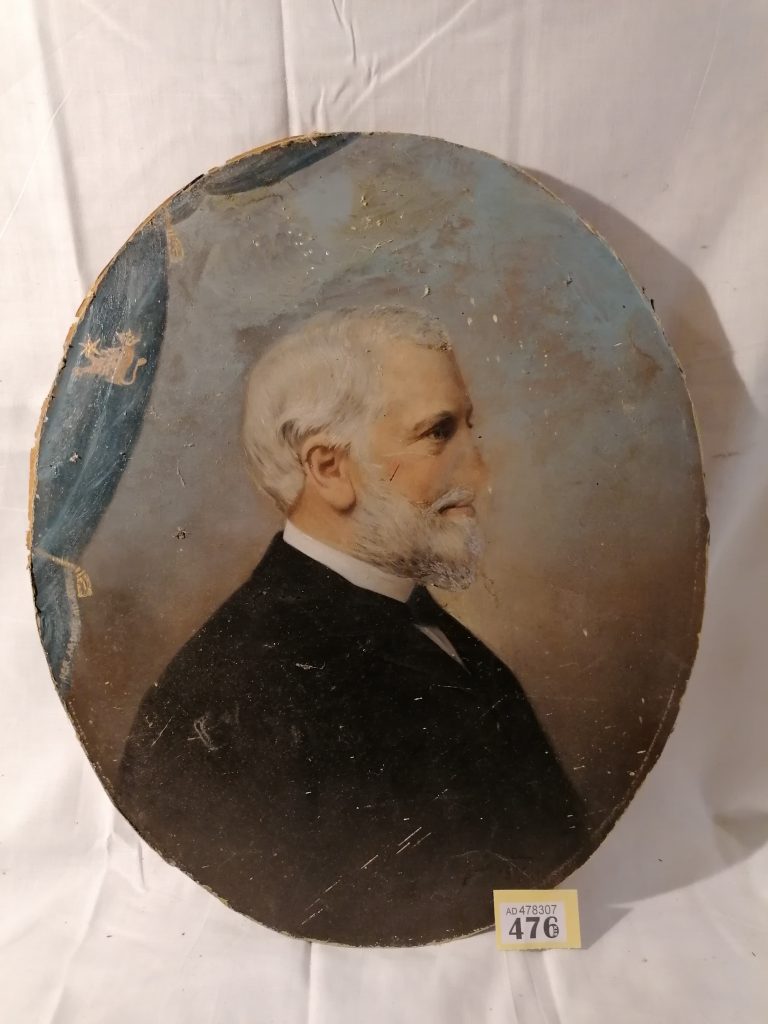

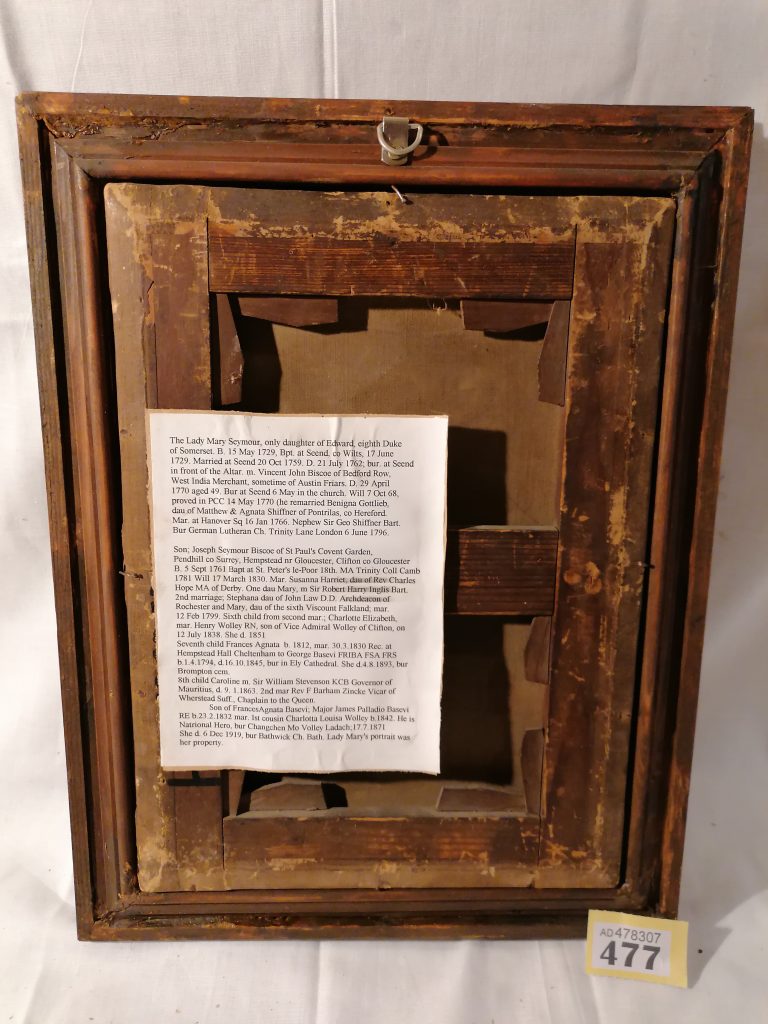

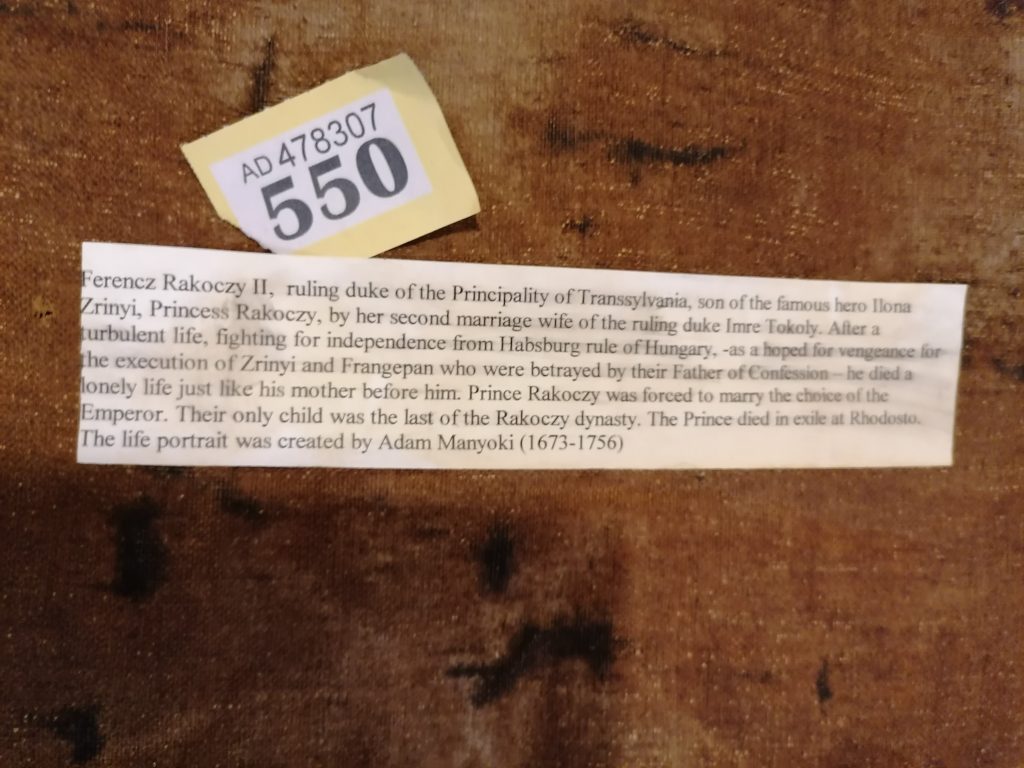

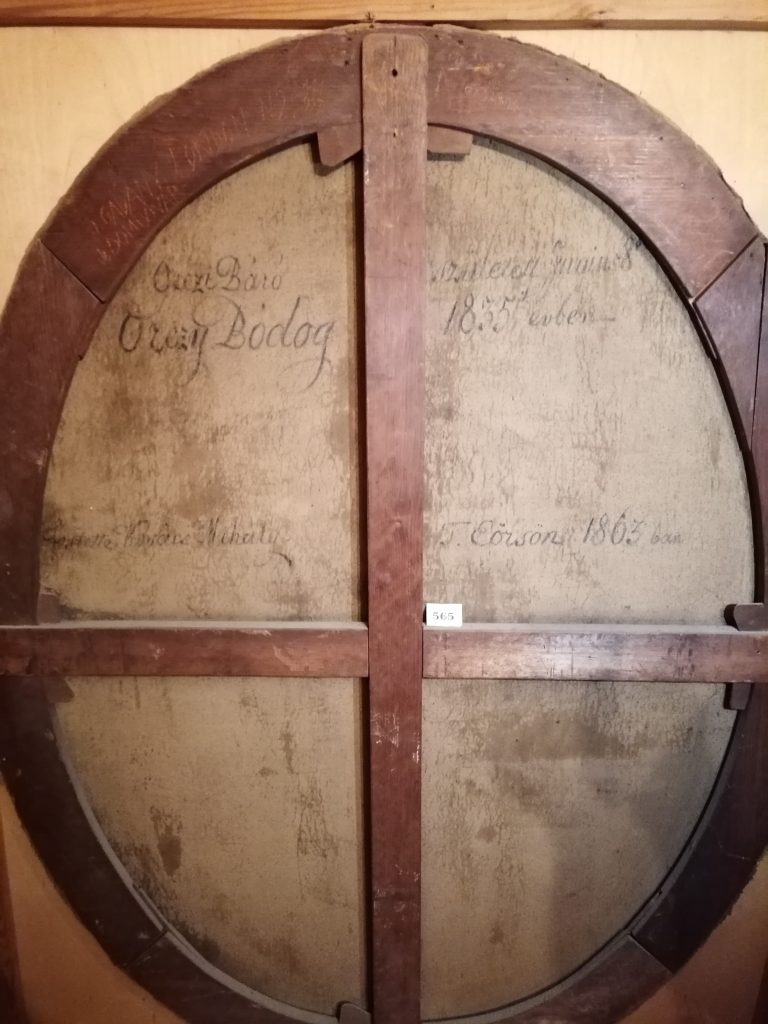

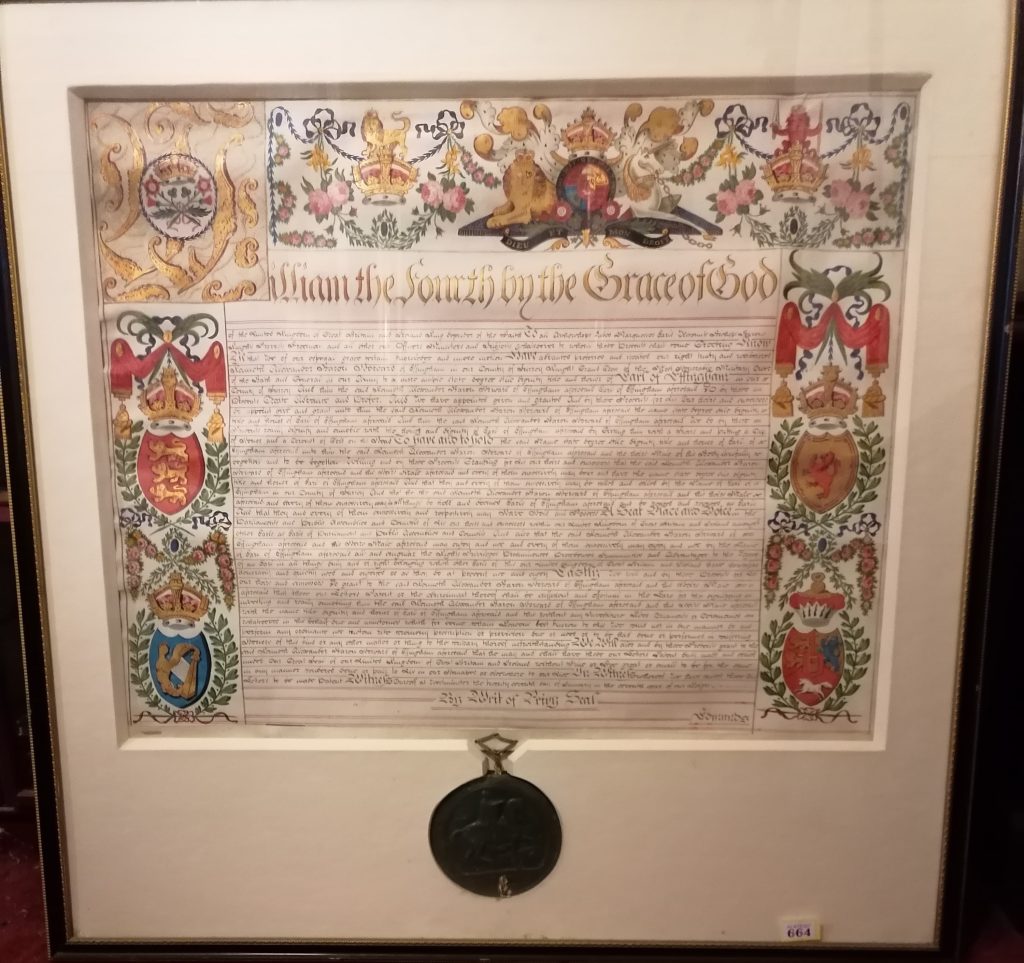

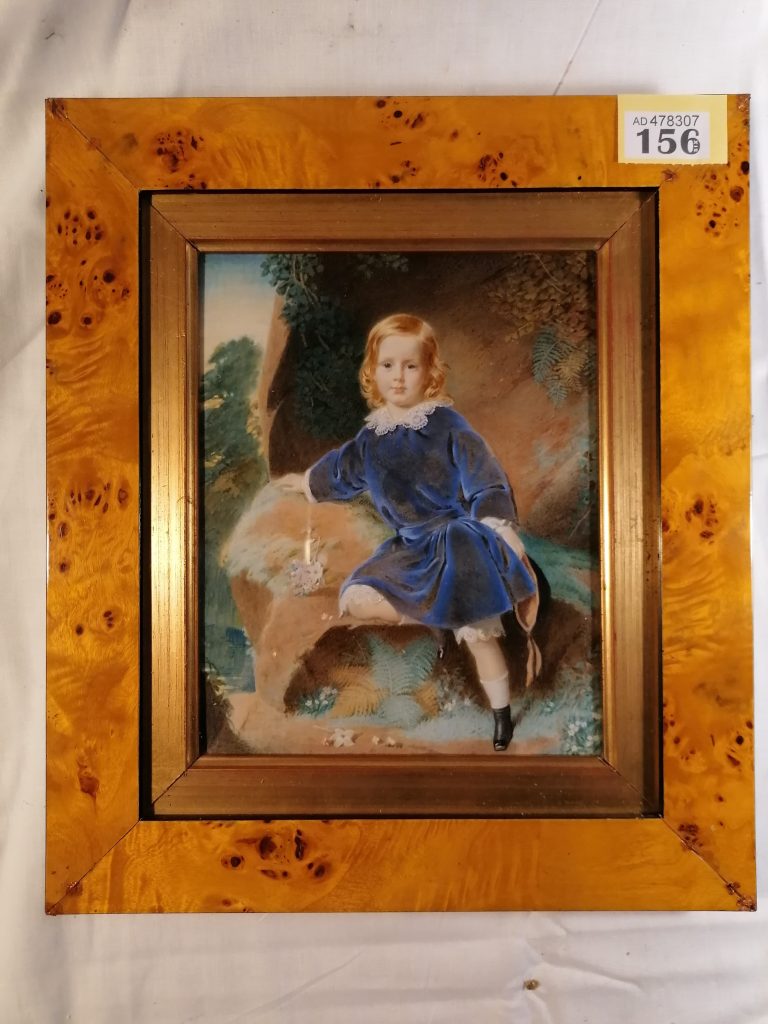

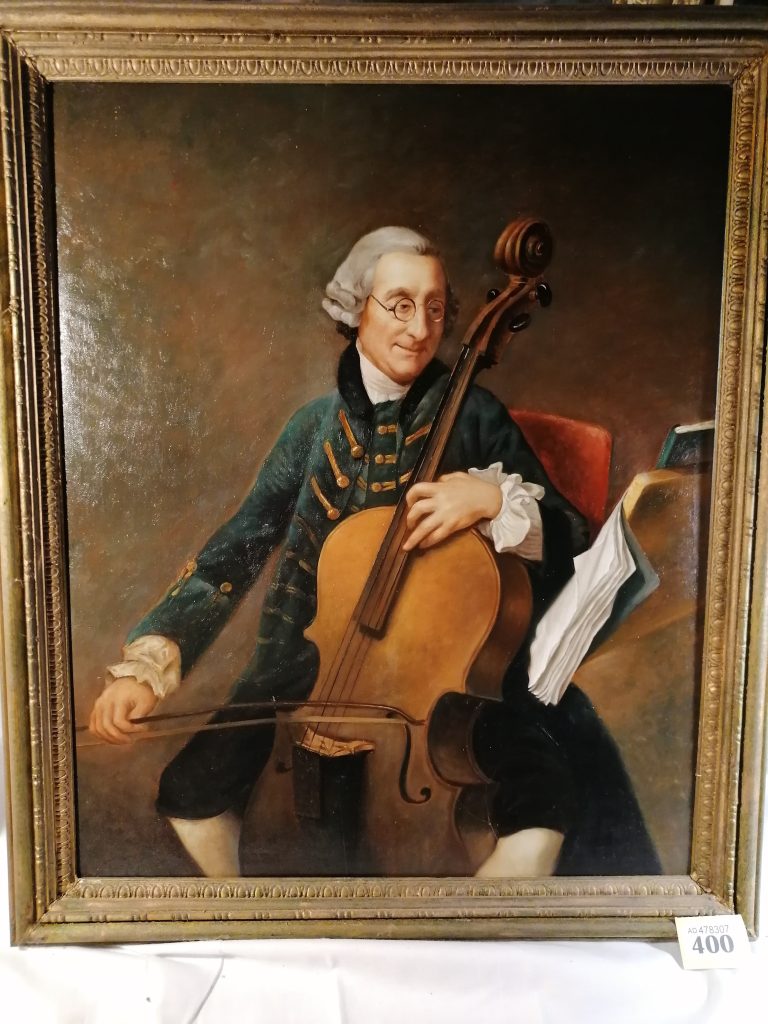

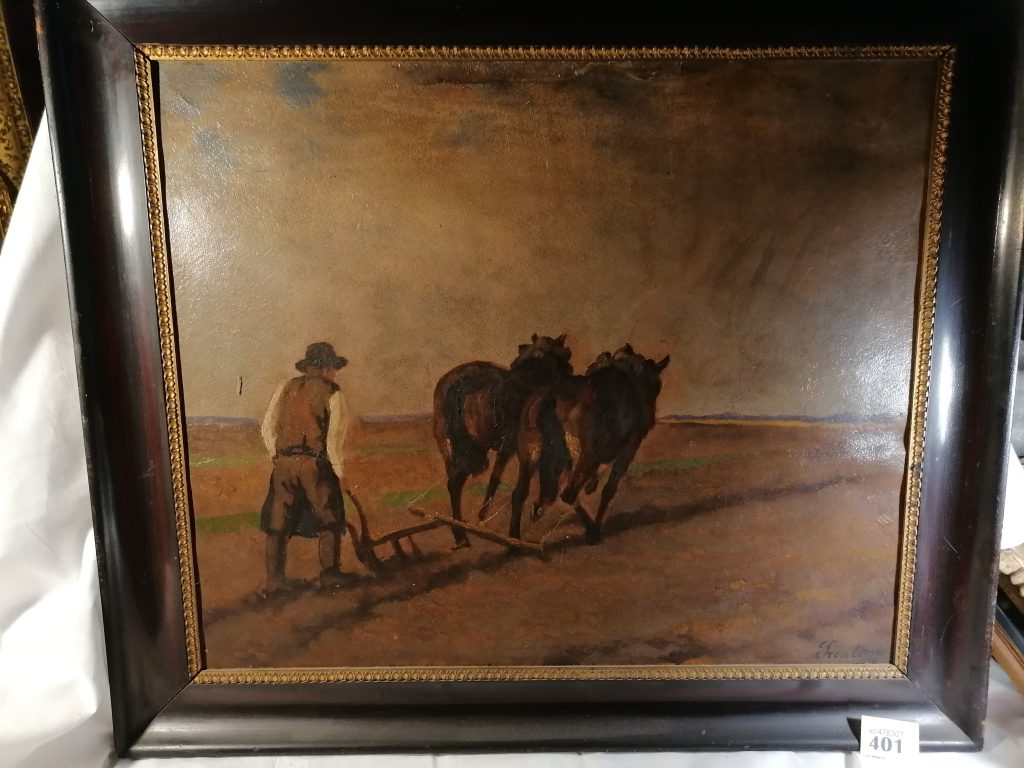

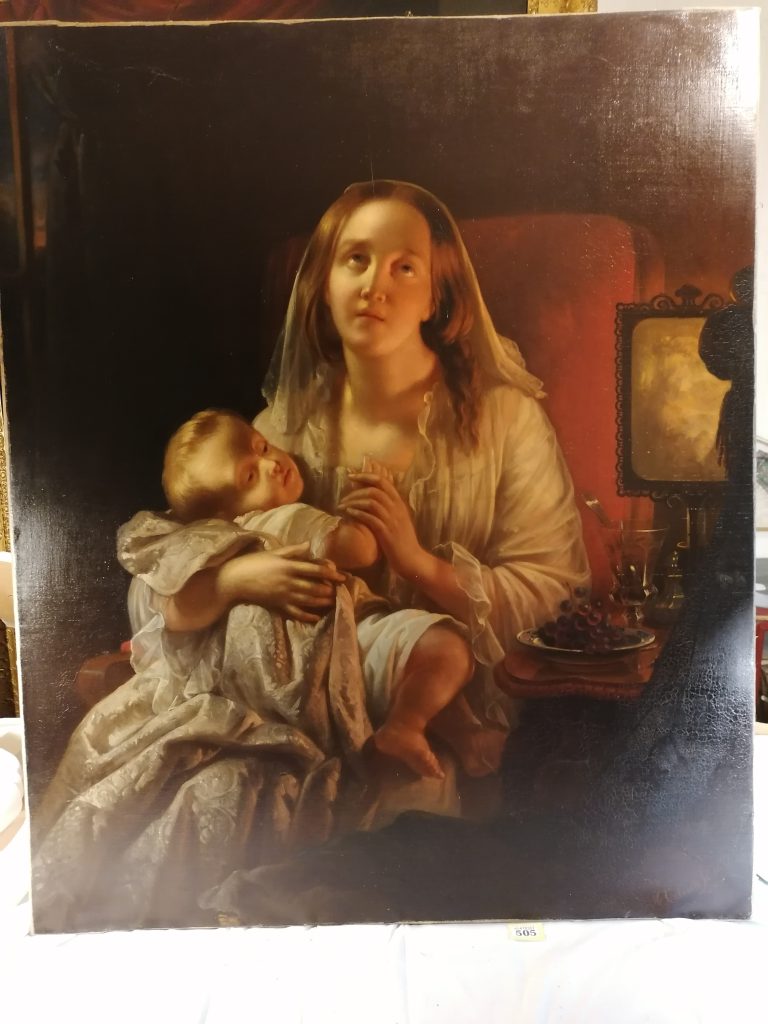

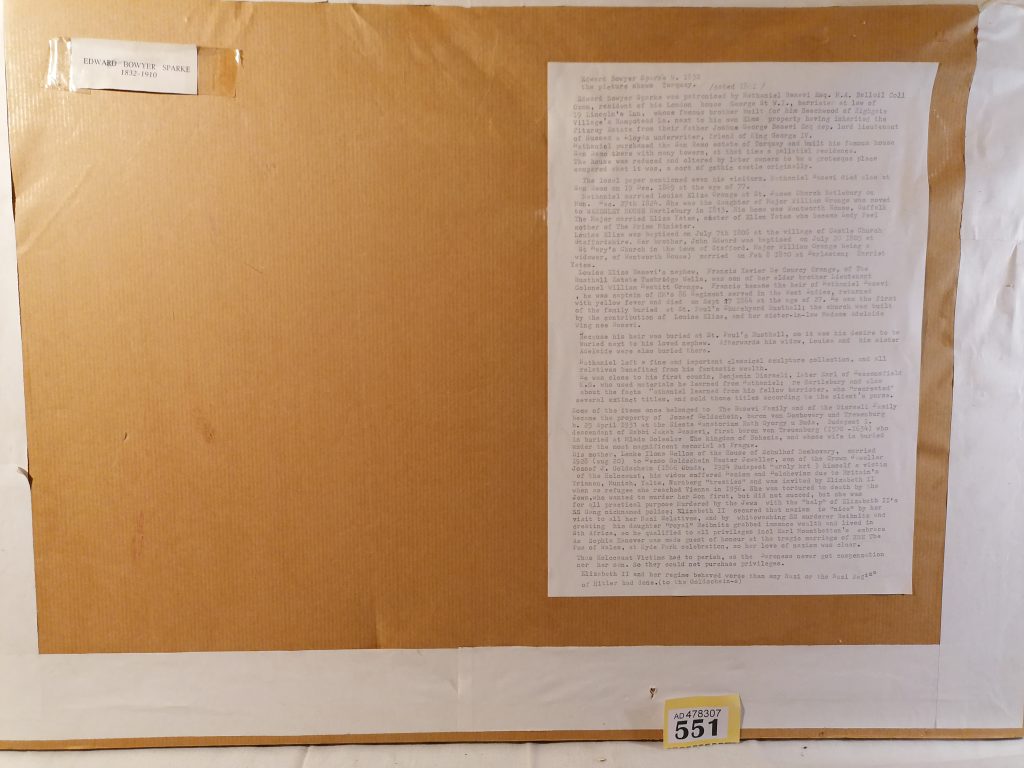

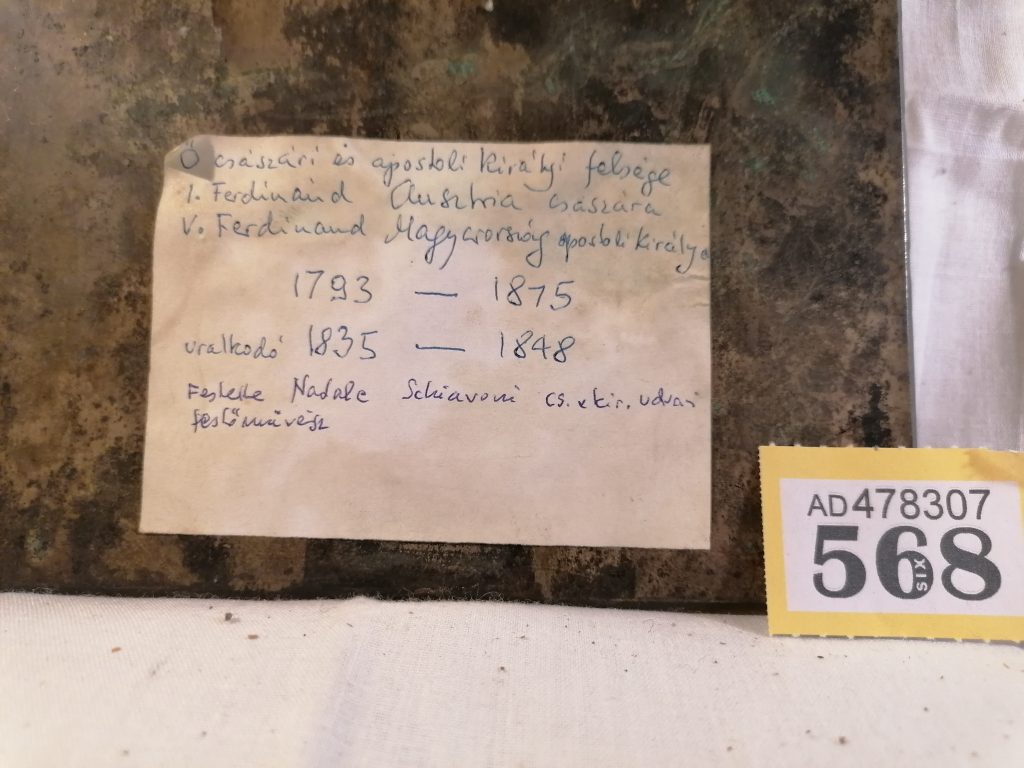

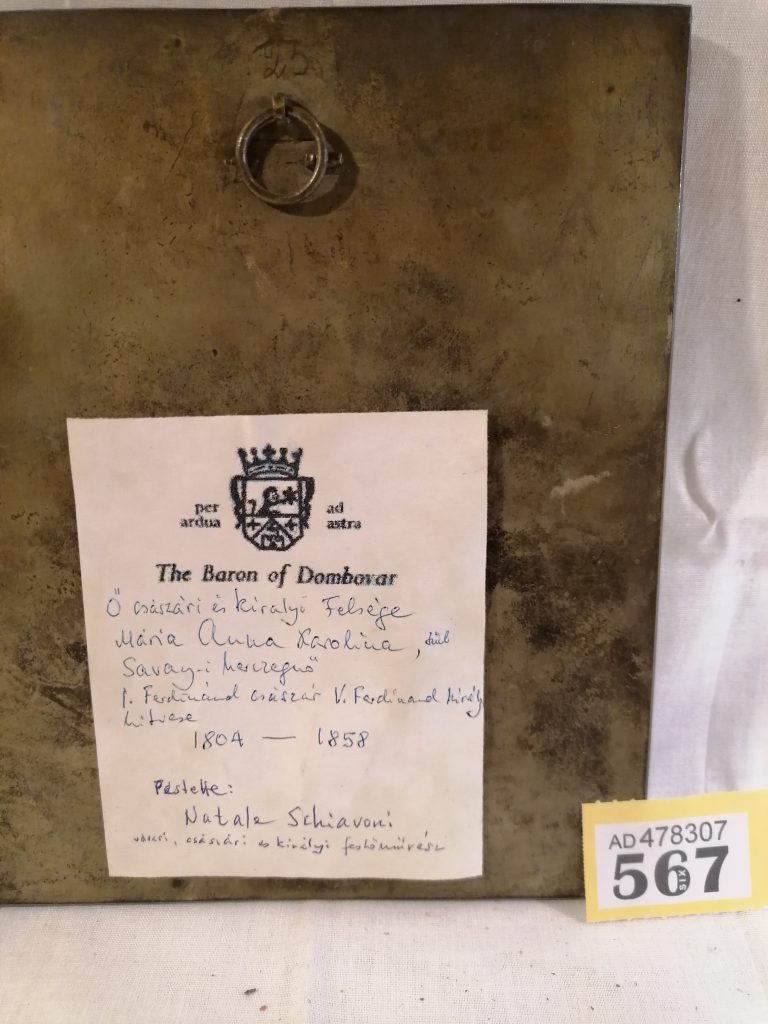

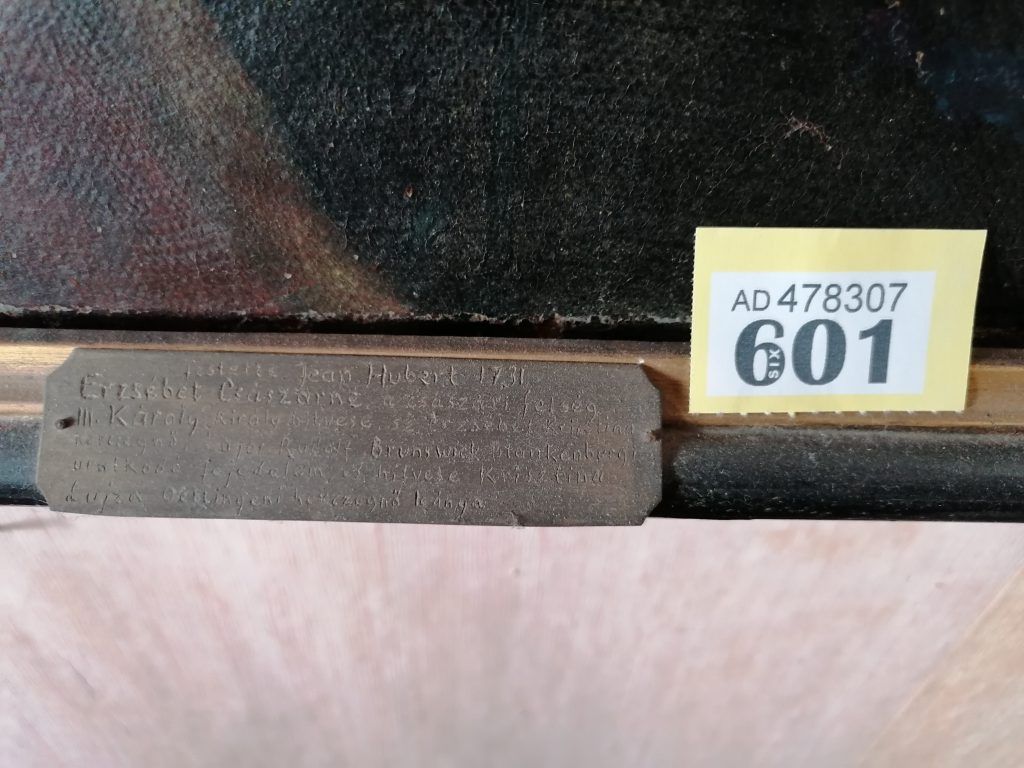

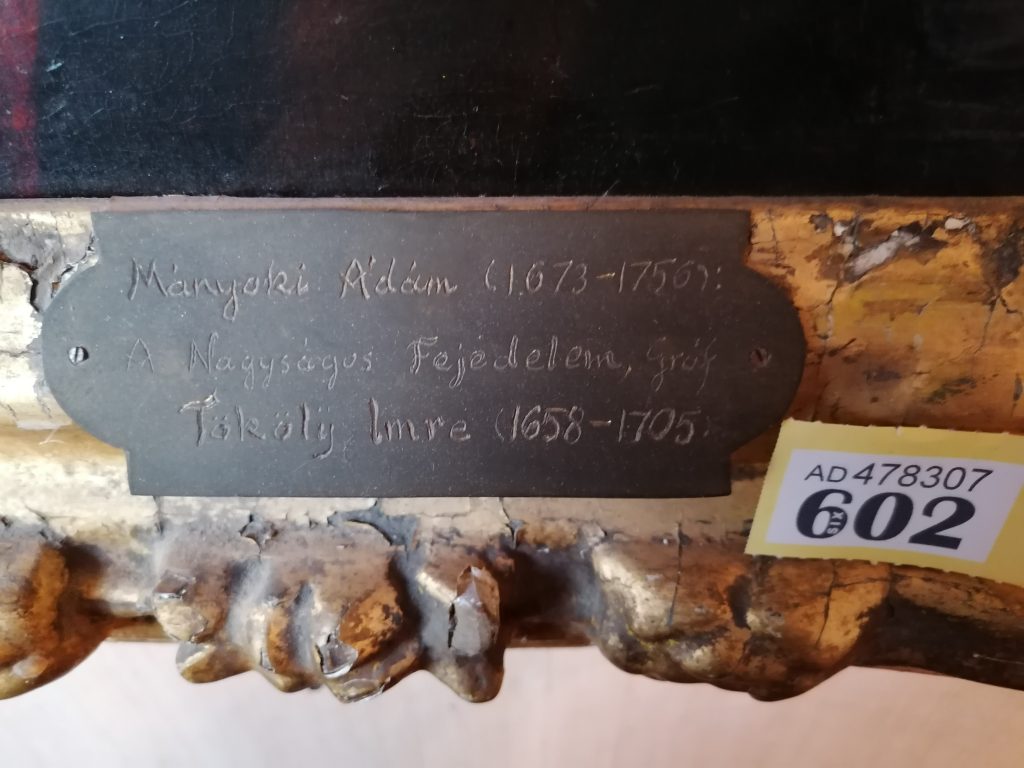

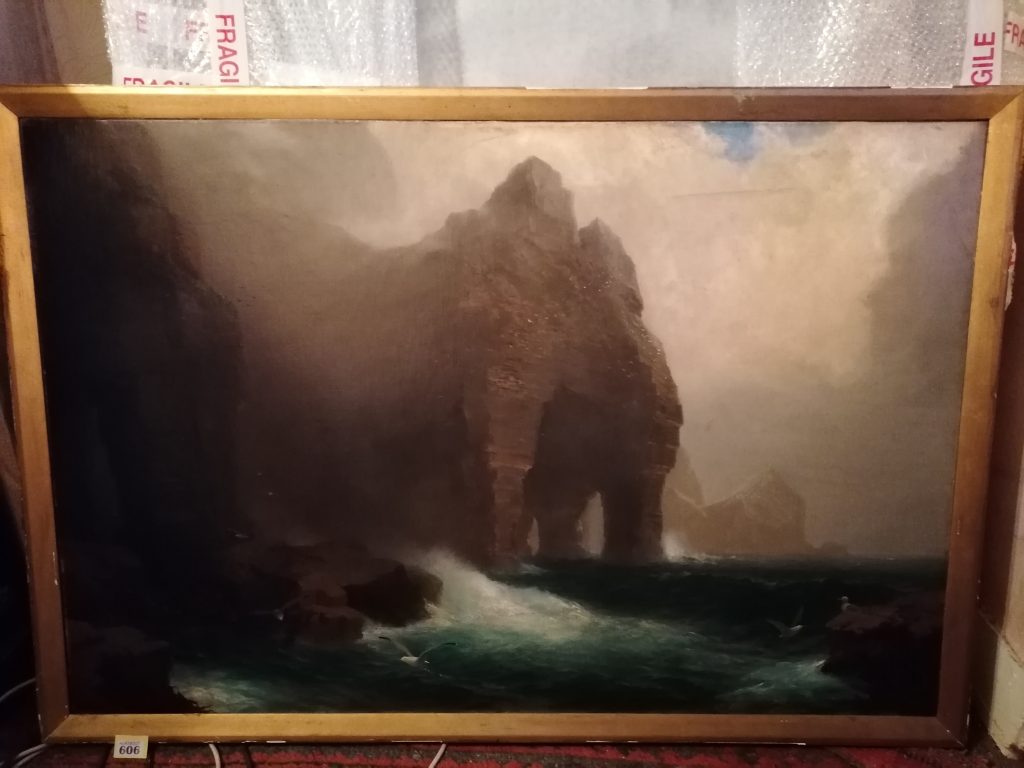

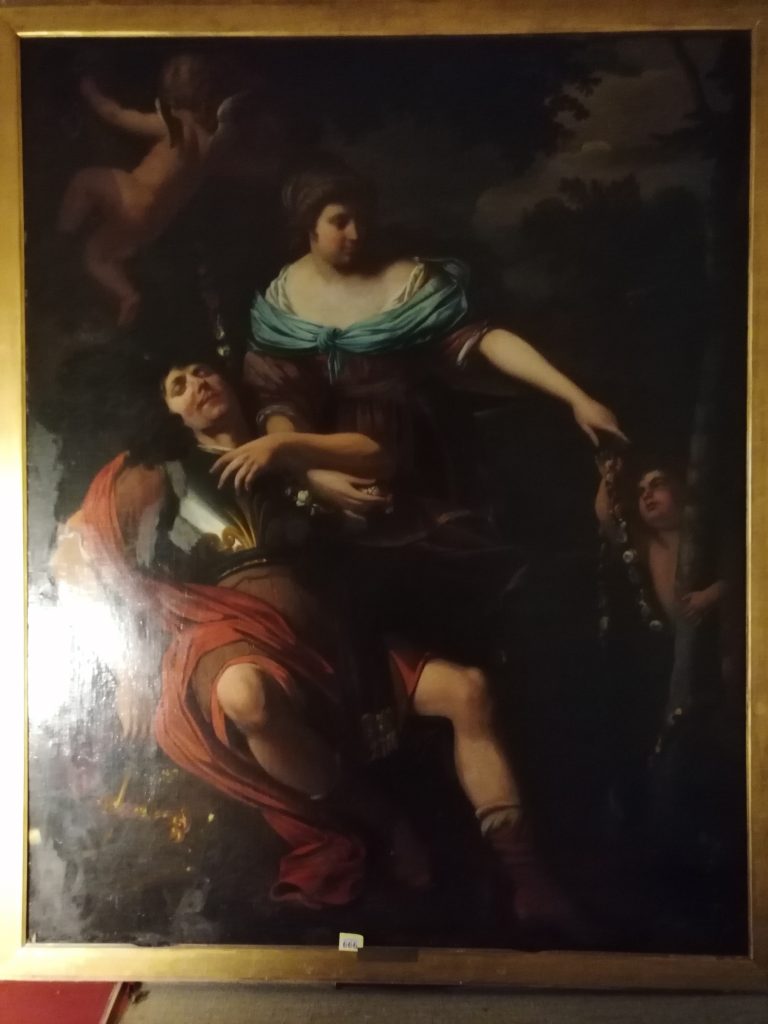

As can be imagined from this account of his life, Joszef’s collection is entirely unique and reflects his many interests. He was most concerned that following his death (which occurred in the summer of 2020) there should be a lasting memorial for his destroyed family. Joszef’s passionate acquisition of objects ensures that the collection makes a fitting memorial. It consists of paintings, books, documents, historical artefacts, ceramics, coins, jewellery and ephemera. Some items are very valuable, and others less so. A few objects had been owned by his family and were stored during and after the war by a distant relative living in the countryside. Joszef eventually had these shipped to London. Other items were purchased by him from individuals or in auctions while he was living in London. All were on private display or in storage at his London home.

The collection revolves around three major themes—the history of his family in a Hungarian context, Benjamin Disraeli and Queen Adelaide—and he maintained that everything was interlinked and belonged together. Having no close relatives remaining, he was intent on finding an institution or organization that would accept the whole collection, make it available for study and never part with any of it. For a year I approached institutions on Joszef’s behalf, most of which were interested in only one part of the collection. That is why Joszef and the executors were delighted by the discussions with Judith Olszowy-Schlanger and the Oxford Centre, and why Joszef eventually agreed to bequeath his entire collection to the Centre. Thanks to the hard work and persistence of Rabbi Smolowitz, one of my fellow executors, the collection has been sorted, documented and packed, and much of it already passed to the Centre. We are honoured and thrilled to know that our dear friend’s collection will be available for scholars, and that his wishes concerning its preservation intact are being respected.

Dr Paul Dakin, On behalf of the Executors of Joszef Goldschein Gadany’s Estate (Dr David Landau, Rabbi Dani Smolowitz and Dr Paul Dakin)